Baldwin to Bailey: "Something has gone really wrong with your modelling"

The Bank of England's MPC gives evidence to the Treasury Committee

Up, up and away

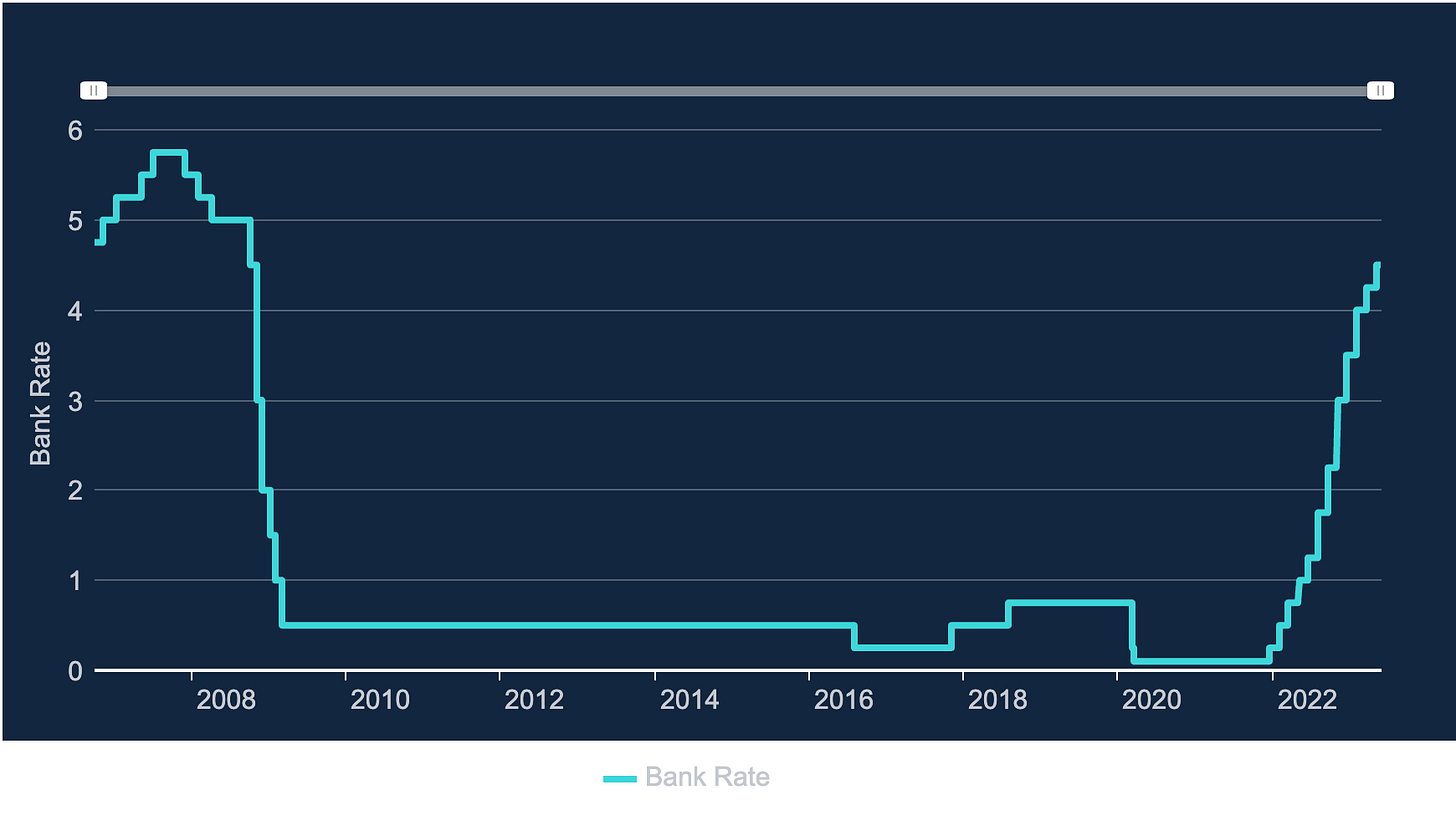

This week Parliament is on Whitsun recess, so I have taken a look back at last week’s Treasury Committee hearing with officials from the Bank of England on their recent decision to raise interest rates again to 4.5% — the highest level since 2008.

On 11 May, the Bank’s monetary policy committee (MPC) voted by a majority for a 12th successive increase in borrowing costs, in its attempt to depress rampant inflation, which has fallen less than expected and currently stands at 10.1%, the highest in the G7.

In a statement, the Bank left open the possibility that the rate would rise again when it next convenes the MPC on 22 June.

Despite admitting that the Bank’s February forecast for inflation was out by 0.8% — a big margin when the target is 2% — Governor Andrew Bailey insisted that he was right to say that the UK had turned the corner on inflation and we won’t return to the peak of 11%.

“Something has gone really wrong”

Committee Chair Harriet Baldwin said that stubbornly high food prices — at the core of persistent inflation — should have been no surprise, given what farmers were saying earlier in the year, adding:

“Something has gone really wrong with your modelling and your network of agents, which is meant to give you this edge in terms of information.”

Bailey said that weather events had been unpredictable factors in high prices, but he also blamed farmers buying up stock at high prices, out of anxiety for the future, thereby locking in high prices for consumers. He confessed the latter factor should have been predicted through the Bank’s “network of agents” who are supposed to inform them of the mood on the ground (or in the fields).

Baldwin reminded Bailey of his infamous comment last year that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine would make food prices “apocalyptic”. So why is he now surprised by high food prices?

Chief Economist Huw Pill said that the Bank was considering whether the size of the shocks to the economy hadn’t changed economic behaviour in such a way as to render the Bank’s forecasting models obsolete, because they are based on the past 30 years of low inflation and relatively few exogenous shocks.

While Pill defended the Bank’s models based on past behaviour in the past 30 years, he rejected the idea that looking at models from the 1970s — before the Bank was set its 2% target and when inflation was high — would be helpful.

However, he wasn’t sure exactly what would be helpful, stating that:

“We can learn from some of the experience of the past, but the world is very different from the past in many respects.”

Baldwin became increasingly frustrated at this point. Accusing the witnesses of complacency due to adopting a narrow historical framework, she said:

“I feel that you may have made the same sort of error as bankers and traders did running into the financial crash.”

It’s not the first time she has been frustrated with Andrew Bailey. I reported in November 2022 on her first time chairing the Treasury Committee hearing with the Bank of England, when she said to Bailey:

“So, was nothing wrong with your models?”

“Behind the curve”

John Baron MP did not accept the emphasis Bailey laid on the exogenous shock of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, pointing to inflation already above 6% and rising before the invasion, while the bank rate remained at 0.5%.

“The facts would suggest that you were behind the curve before the invasion.”

Bailey explained that rates were kept low at that point to deal with a countervailing fear: namely, that the end of the furlough scheme would cause massive unemployment.

Keeping the rate low might encourage employers to hold on to workers or they could borrow cheap money to do so. He admitted that, as we now know, that wave of unemployment did not come — the forecast was wrong.

Other, deeper problems with the UK labour market were, however, revealed — problems that have also contributed to stubborn inflation rates.

External member of the MPC, Professor Silvana Tenreyro, said that if the bank rate had been raised quicker and earlier, say in summer 2021, the impact on unemployment would have been greater than the relative benefit to reducing future inflation.

“Inflationary psychology”

Anne Marie-Morris MP wanted to know about the possibility that changes in economic behaviour have rendered models of the impact of monteary policy on the economy obsolete.

What are those changes?

Huw Pill said that maybe consumers, retailers and banks did behave differently when interest rates were in double digits, but Marie-Morris hit back that the issue is probably cultural — suggesting the pandemic had given people a false sense of security that the Government would pick up the tab at the end of the night.

Pill rejectected that as “conjecture” but accepted that people expecting persistent inflation acted in such a way that generated further persistent inflation — a vicious cycle of “inflationary psychology”.

Bailey added that whereas during the pandemic they had feared “scarring” on the economy due to the collapse of firms and stock, the real scarring may have come at a cultural-psychological level in terms of unforeseen changes in behaviour in labour supply and economic participation.

That is of course very difficult for the Bank of England to model on its econometric charts.

“Have you done any work on whether economic forecasting is dead?”

Dr Mann, another external member of the MPC, said that she had consistently voted against the majority and in favour of quicker hikes in the bank rate. She claimed that she had noticed the problem with the models that the others were just discussing much earlier:

“The model was never telling us about persistence, primarily because it was estimated on historical data. It is linear and, therefore, cannot address some of these behavioural changes that we observe at the micro level.”

To this, the (appropriately) sardonic Andrea Leadsom MP asked:

“Dr Mann, that was really interesting. Have you done any work on whether economic forecasting is dead?”

And, given that Dr Mann’s views had been aired in speeches but not conceded on the MPC, she also asked:

“does the MPC work as it is intended to do, or is it ending up with the wrong results, in your opinion?”

In response, both external members defended the MPC and its use of forecasts.

It seems, there is a general crisis of economic forecasting in the wake of the pandemic and serveral other events.

As I have reported previously, the Office for Budget Responsibility has also had to admit recently that its forecasts have been widely inaccurate and its picture of the future is deeply uncertain.

There have been changes to the estimation of R&D spending in the UK economy due to slight changes in how that figure is calculated.

The ONS’ attempts to measure immigration are, of course, not a sure science either.

What is the significance of having such variable and sensitive forecasts, on which so much policy and politics is grounded?

The Bank of England’s MPC itself relies on forecasts from the ONS and the OBR. For example, Dr Mann said that she would not comment on supply-side policies, only that she feeds the OBR assessment of their economic impact (a highly uncertain assessment as we have seen) into her own modelling.

And Bailey refused to answer Danny Kruger MP’s question about whether high levels of immigration depressed investment in capital and labour (essentially, machinery and up-skilling/training), because he “does not comment on immigration” (that’s politics) but he follows the (problematic) numbers released by the ONS.

Politics

Whether this means economic forecasting itself needs a rethink — with more scenario testing or other ways of accounting for psychological-behavioural economic changes — I cannot say.

But it does seem to suggest that politicians who make dramatic arguments on the basis of economic forecasts — and those who insist that policies launched without them are beyond the pale — might need to be taken down a notch.

Politics requires a broader judgment than “follow the stats”, because the stats, it turns out, are problematic.

The current Prime Minister pinned his whole future on “five promises” in January, including to halve inflation by the end of the year. Many at the time thought that was an easy win. But the most repeated word in this Treasury Committee hearing, as we mark the half-way point in the calendar, “persistent”. That might start to make him worry.

Could persistent inflation turn into deflation?

The source of the persistant inflation is still elusive, however.

Bailey told the Committee that there was no hard evidence that strikes were keeping inflation high. Nor was he certain that there was what Labour MP Angela Eagle called “greed-flation”, with profit margins keeping inflation high.

But he was certain about one thing:

“We do believe inflation is going to come down; we believe that strongly.”

Despite that, with all this “persistance”, we may well see the bank rate go up yet again later in June. And the effects of all these bank rate rises on the economy — and on people’s lives — are slow to come through.

For instance, Bailey told the Committee about the lag in the impact of rate rises on home reposesssions and mortgage defaults because fixed-rate mortgages protected many households from feeling the pinch straightaway. Only one-third of the impact has come through, he said.

But when fixed-rate resets happen in the second half of the year, the impact will become more pronounced.

Professor Tenreyro, who is stepping down from the MPC shortly, has consistently voted against rate rises for that reason:

“We know there are important lags in the transmission of policies […] My assessment is that, conditional on this path for market rates, we will undershoot the target.”

In other words, there is the potential that when the impact of all these rate rises land, we could have deflation.