With all eyes on the Budget yesterday, Parliamentary Insight is taking a different look at the UK’s economic situation by reporting the evidence session held by the Treasury Committee on Wednesday with Andrew Bailey, Governor of the Bank of England, and other members of its Monetary Policy Committee.

The role of the BofE, its monetary policy and the question of its independence and what that means are key factors in understanding how we got to yesterday’s Budget.

I will follow up next week with the more detailed debate on the Budget, which will follow in the coming days, allowing more scope for MPs to respond to specific parts.

Governor Bailey

The Bank of England has come to the fore in the UK’s economic crisis around inflation, the mini-Budget and the fall of Liz Truss’ premiership.

At the start of this month, the Bank’s MPC voted to raise interest rates to 3% and forecast the longest ever recession for the UK economy — moves which have heavily influenced the work of Jeremy Hunt in preparing his Budget.

Despite inflation currently being more than 9 points higher than the Bank’s 2% target, the Governor Andrew Bailey has had something of a PR coup for a man miserably failing at his only job, managing to position himself as weary but sensible against the chop and change of political chaos at the top of the Conservative party.

One of the primary ways in which the Bank of England is held to account is through the House of Commons Treasury Committee.

The Chair of that Committee during the inflation mini-Budget crises has been Mel Stride, an ally of Rishi Sunak who was arguably soft on the Bank in order to attack Truss and Kwarteng. He led the charge for the Office for Budget Responsibility after it was shut out of making a forecast on the mini-Budget.

Sunak duly rewarded Stride with a Cabinet position as Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, just in time for “compassionate austerity”.

Chair Baldwin

In her first rodeo as his successor, Harriett Baldwin wanted to show she has some teeth, politely.

Baldwin kicked off the session but asking Bailey directly why the inflation target has been so badly missed. An obvious question.

Bailey waffled and squirmed through blaming the tight labour market, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and shocks to supply chains after Covid.

Baldwin pressed him:

“So, was nothing wrong with your models?”

Bailey insisted that none of those factors could reasonably have been foreseen a year ago, and even if they had, it would not have been possible to raise interest rates during the pandemic.

He is responding here to the implicit criticism in Baldwin’s question, that the Bank of England should have raised interest rates more slowly at an earlier point and thus would have not had to do so this dramatically now.

Wasn’t it obvious, Baldwin asked, that loose monetary and fiscal policy coupled with sharp quantitative easing would create the danger of runaway inflation?

This prompted some of the more ridiculous smoke and mirrors from Bailey who said,

“We don’t have hindsight when we set policy”.

And his deputy, Ben Broadbent came up with this oh so profound statement:

“the fact that something happened that was not forecast doesn’t mean the forecast was wrong; it means we live in a highly uncertain world”.

One wonders why these people are paid hundreds of thousands of pounds of taxpayer money to work these things out if at the end of the day they can say effectively, “we weren’t wrong, we were just different to the reality”.

Early warnings ignored

Baldwin defended her line of questioning by saying:

“I wouldn’t be asking these questions if I hadn’t in real-time been asking about some of the inflation risks before inflation jumped out of its box… I was worried about it as the record will show”.

Indeed, the record does show that in response to the 2021 Spring Budget, Baldwin expressed fears of bond markets and inflation making a toxic cocktail.

In May 2021, Baldwin told the House:

“As someone who traded the bond markets… I know that the bond markets can turn on a dime. With the amount of fiscal stimulus and monetary stimulus that we have in this country, I think there is quite a strong risk that we might spark inflation. We saw inflation in America in the statistics that came out this week, and we saw the way in which the markets react to it. We are running quite a large risk in terms of our deficit, with the potential for interest rates to go only one way from here: upwards. That could really damage the brighter future for the next generation.”

And in March 2021, Mel Stride told the House:

“Andy Haldane, the Bank of England’s chief economist, has pointed to this risk [of rising inflation] recently. We know that if inflation increases and spikes, the Bank of England would need to tighten monetary policy to try to keep inflation under control. We would have bond markets in which the Government and the Bank of England were potentially both sellers, with increased upward pressure on interest rates and all that would follow.”

But in the Bank of England MPC forecast of May 2021, they wrote:

“In the central projection, CPI inflation rises temporarily above the 2% target towards the end of 2021, owing mainly to developments in energy prices. These transitory developments should have few direct implications for inflation over the medium term [i.e., 2-3 years], however. In the central projection, conditioned on the market path for interest rates, inflation returns to around 2% in the medium term.”

Inflation in January 2022, before the invasion of Ukraine, was 5.5%.

Tight labour market

The one point Bailey conceded was that they might have foreseen the tightening of the UK labour market as a spark for inflation.

Did you miscalculate the effects of the end of furlough, then? asked Baldwin.

No, the MPC officials insisted, the UK presents a more inscrutable puzzle than that.

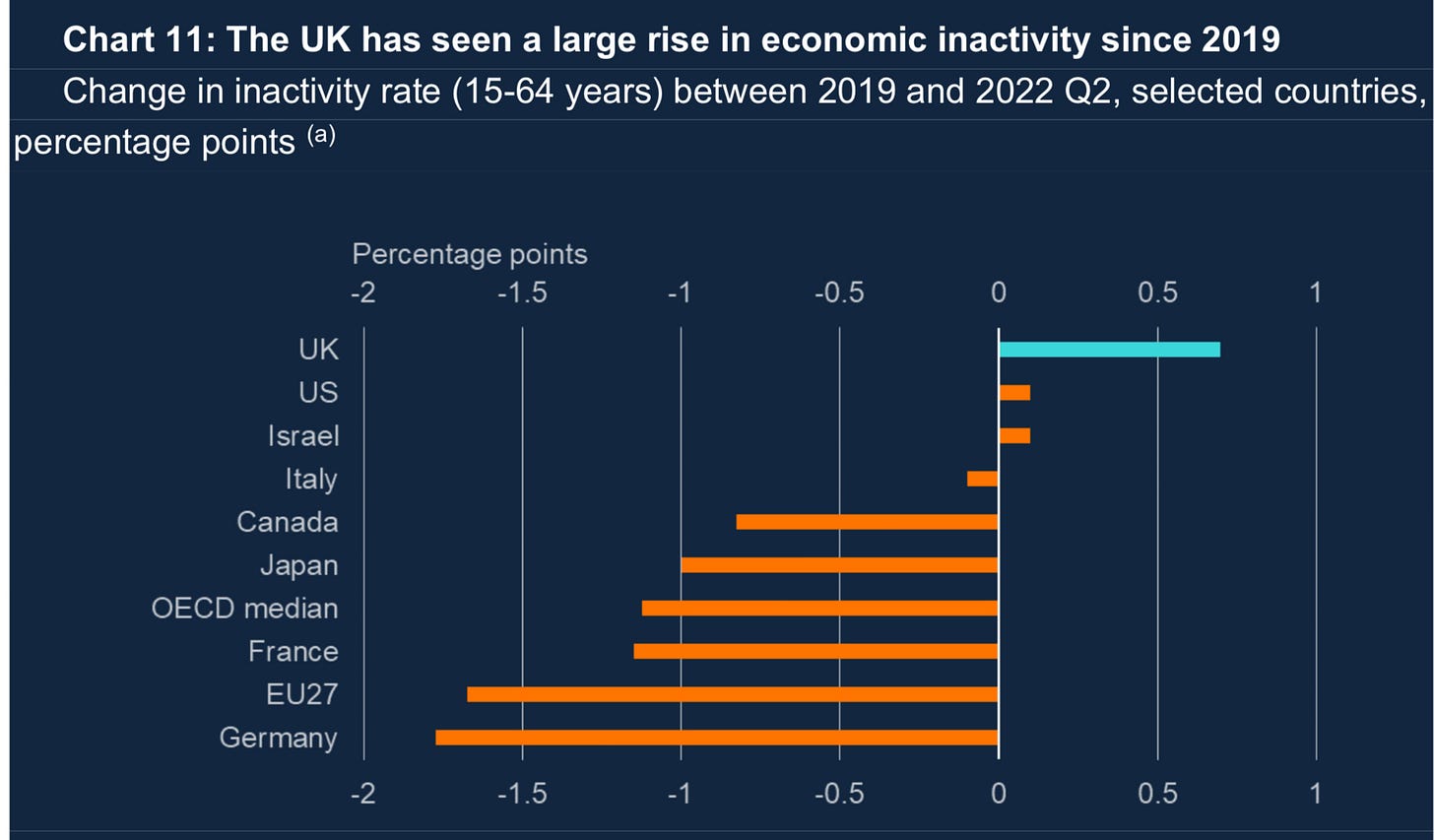

They referred to a speech given by MPC member Jonathan Haskell to the Bank of Israel last week, in which he showed the outlier position of the UK’s labour participation rate between 2019 and mid-2022, which is much worse than comparable countries.

Haskell states that this is due to 17% of the working-age population being long-term ill, of which an insignificant amount is due to long-Covid — a shocking thought, and one that perhaps isn’t satisfactory as an explanation.

Nonetheless, Haskell concludes:

“while the energy price shock might fade, the shortage of workers and labour market tightness, and thus upward pressure on inflation from wage growth, might persist in the longer-term. This could leave inflationary pressure in the UK for longer than other countries.”

Fellow MPC member Catherine Mann told the Committee that the UK’s labour problems are hard to interpret. If people are not working but inflation is hitting their pocket, how are they managing?

“That is a very significant puzzle.”

Perhaps they are not managing, but we are yet to notice the knock-on effects in social degradation. As Deputy Governor Ben Broadbent blithely noted:

“historically on average recessions are regressive; it is the less well paid that are more likely to lose jobs in a downturn. These huge rises in import prices happen to be in areas which form a larger part of the consumption basket for less well off people: energy and food.”

Swati Dhingra, also of the MPC, said the resulting damage is long-term:

“Typically those who enter the labour market in a recessionary environment end up with perpetually lower wages. That risk is strong here.”

Labour caught between Brexit and the boffins

On the Committee, Labour’s Rushanara Ali seemed to know the cause of our woes: the B-word!

She quoted former MPC member Michael Saunders, who told Bloomberg TV this week:

“The UK economy as a whole has been permanently damaged by Brexit… If we hadn't had Brexit, we probably wouldn't be talking about an austerity budget this week. The need for tax rises, spending cuts wouldn't be there.”

While current MPC members would never make such political statements publicly, Swati Dhingra said that Brexit had caused a “big stagnation” in the UK economy, especially looking at trade, with Catherine Mann adding that small firms have been damaged the most.

They seemed to agree that this has had made a global inflation crisis much worse in the UK, though they didn’t make any comments about the relation between Brexit and labour supply.

Ali also pressed the Governor of the Bank on the mooted Government amendment to the Financial Services and Markets Bill, which would give vague powers to the Minister to require financial regulators to make, amend or revoke rules in matters of significant public interest.

Andrew Bailey followed his peers at the big regulators by saying he thinks this would be a bad idea and would further damage the UK’s international reputation and economic stability.

Ali characterised this potential move by the Government as being part of a trend that threatens the independence of the Bank of England, going back to Liz Truss’ infamous comments over the summer.

But Ali had to catch herself there. Of course, she said, I have been critical of decisions the Bank has made in the past.

But now she found herself saying that all of the Bank’s recent decisions have been “necessary”.

This indicates part of the political problem for Labour, as was highlighted by the fallout from the mini-Budget.

If they keep using the position of Remainers on the one hand and financial markets experts (including the OBR and the BofE) on the other to attack the Government’s policy, they might find they have left themselves remarkably little wiggle room if they come to power at the next election. In defending the independence of the Bank of England from a probably immaterial threat for political gain now, they may erode their own political independence in the future.

Andrew Bailey, for what its worth, despite Baldwin’s best efforts at playing the stern Select Committee Chair, seems untouchable.