Office for Budget Uncertainty

The Treasury Committee scrutinises the Budget and the OBR's forecast

On Wednesday afternoon, away from the circus in the Grimond Room, starring ringmaster Harriet Harman and moping lion Boris Johnson, over in the Wilson Room (yes, both rooms named for 1960s party leaders), another Harriett (Baldwin: two Ts; no relation to Stanley) led the Treasury Committee in a round of questions to Richard Hughes, Chair of the OBR, and the other two members of its Budget Responsibility Committee, Professor David Miles and Andy King.

Ancient history

The OBR was founded in 2010 by George Osborne, then Chancellor in the coalition Government, in a critique of the outgoing Labour Administration, to make economic and fiscal forecasting independent of Government.

Since then, the OBR has published forecasts each year with the Chancellor’s Budget and the Spring statement. Until last year, when Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng decided not to allow the OBR to publish a forecast alongside their October non-Budget growth strategy.

This was widely denounced as “irresponsible” — responsibility being the main theme here. Kwarteng and Truss protested that the OBR’s forecasting could not adequately account for the type of changes they sought to introduce and its modelling had been captured by a tired economic orthodoxy — Osbornomics — which they wanted to smash.

It’s a political question that is worth asking, but since they failed to bring even a majority of their own party with them, it has probably been rendered taboo for at least the next decade.

From the Tory Backbenches, then-Chair of the Treasury Committee, Mel Stride, led the charge on behalf of the OBR, the gilt markets went haywire… and the rest is history.

Last week’s Budget

In his Budget last week, sensible Jeremy Hunt couldn’t get enough of the OBR:

“I start with the forecasts produced by Richard Hughes and his team at the independent Office for Budget Responsibility, whom I thank for their diligent work.”

The OBR forecast, he said, showed he was doing all the right things: avoiding a technical recession, bringing down inflation, meeting the fiscal rules on public sector net debt and borrowing, and boosting investment.

Yet, the OBR forecast was also evidence for Keir Starmer’s rebuttal:

“According to the International Monetary Fund, we are the worst-performing country in the G7 this year—a prediction today confirmed by the Office for Budget Responsibility, with growth downgraded in the years to come… The OBR makes it clear today that things do not look any better in the long run.”

Treasury Committee Chair Harriett Baldwin continued the work of her predecessor and welcomed the OBR’s report:

“The Treasury Committee welcomes the fact that the Budget is accompanied by forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility. We think it is important that that stands alongside a Budget. It is a key part of the independent framework for Chancellors and we will be taking evidence from the OBR next week on the underlying assumptions behind its forecasts.”

It seems the OBR has become, like St Paul, all things to all people. Whether that is to save them or itself is another matter.

Illusory headroom

Baldwin began the evidence session by asking the OBR whether the Budget was a responsible one. It had technically met the rules, the witnesses said, but there were several loopholes for Chancellors to wriggle through.

One such loophole is fuel duty. Richard Hughes reiterated to the Committee exactly what he wrote in the OBR forecast’s executive summary.

The Chancellor has £6.5 billion in headroom when it comes to public sector net debt. That might sound like a lot, but the OBR says it is the smallest amount since 2010. Of that £6.5 billion, £4 billion is accounted for by increased fuel duty receipts when the Chancellor reverses the temporary 5p cut to fuel duty and sets it to increase with RPI, as he has promised to do in 2027-28, the last year of the forecast period. Except everyone knows that is never going to happen.

“Cancelling these planned increases, as every Chancellor has done since 2011, and instead holding fuel duty at its current rate would, in itself, more than halve the Chancellor’s headroom.”

Other projected measures that are not accounted for in that £6.5 billion are the targeted Defence spending of 2.5% of GDP, a return to 0.7% of GDP spent on foreign aid and making the temporary tax relief on capital investment — “full capital expensing” — permanent. According to Richard Hughes, fulfilling those aspirations would cost £15 billion.

While the full capital expensing measure was touted as a central plank of this “growth budget”, Professor Miles told the Committee that the cumulative level of investment across the whole five-year period of the forecast was unchanged, because the temporary tax relief was forecast to bring forward investment into the first three years, followed by a drop off below the otherwise expected level, once the temporary measure then expired

Inflation forecasting

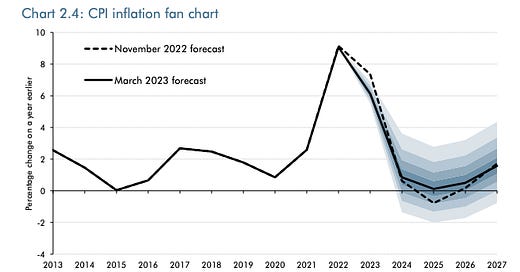

The OBR forecast — handily for Jeremy Hunt — that inflation will fall to 2.9% by the end of the year (and 0.9% in early 2024!) far exceeding the Prime Minister’s goal of halving it from its peak to around 5%.

However, just before the OBR officials came before the Committee on Wednesday, the Office for National Statistics published figures showing a surprise jump in inflation, which led the Bank of England to announce yesterday that it would raise interest rates again to 4.25%, the highest since 2008.

John Baron MP invoked the spirit of economist John Galbraith who famously compared economic forecasting to astrology. How could the OBR be so sure, given all the global uncertainty, that inflation would fall so quickly?

Professor Miles said that, well, actually, they weren’t so sure. That figure was largely based on the futures markets for oil and gas. And who knew what would really happen with that. The OBR forecast measures the degree of uncertainty not based on real-world liabilities but on an average of past forecast errors, and then goes on to state (para 2.14):

“the average of past forecast errors is not always a good indicator of the degree of uncertainty at specific points in time, especially following very large shocks such as last year’s energy price rises. The distribution around our 2023 CPI inflation forecast is therefore likely to understate the degree of uncertainty in the current environment of very high and volatile energy prices.”

You can forgive Mr Baron’s incredulity.

Back to work

There were similar difficulties forecasting the impact of Hunt’s “supply-side” policies, meant to deal with Britain’s curious case of high economic inactivity, including more funding for childcare costs, to get mothers back into the office quicker, measures to support employment for people with disabilities, and the removal of limits on millionaires’ pension pots, to keep them in work longer.

The OBR expects the new 30 hours a week of free childcare for working parents of nine-month to two-year-olds to have “by far the largest impact on potential output in this Budget.”

It is expected to encourage 60,000 people back into work and slightly increase the hours worked by those young parents who already work.

Former Tory leadership contender Andrea Leadsom was curious as to how that figure was arrived at. It was not from surveying people — something the OBR was unable to do — but comparing the impact of other similar policies, primarily the existing childcare provision for children over the age of three.

Leadsom noted the obvious: that parents of babies below three will have very different tendencies to return to work than those with a four-year-old.

The OBR forecast admits that:

“Our central estimate of the increase in labour supply as a result of the policies announced in this Budget [110,000] is very uncertain, and a plausible range could be as high as 240,000 or as low as 55,000 based on alternative plausible assumptions.”

Even if 110,000 do return to work, the number apparently lost since Covid from the workforce is 500,000, and, as the witnesses admitted, the reason for that missing group of workers remains a mystery.

There was also scepticism that the removal of the limit on £1 million pension pots would help improve the workforce.

The OBR says:

“Changes to the lifetime allowance and annual allowance on pension contributions increase employment by around 15,000 by removing some financial disincentives to continuing in employment for those with large pension pots.”

But the witnesses told Labour MP Emma Hardy that there was also great uncertainty about that number.

Labour have tried to use this policy to paint the Tories as giving handouts to their rich friends, with Emma Hardy scoffing that it made George Osborne (who had implemented the old cap) seem like a socialist.

The OBR witnesses did not have a view on this… after all, that’s politics.

But it goes to show how confused we all are after the failure of the Conservative party under Truss and Kwarteng to take us beyond Osbornomics and the OBR. The blow wasn’t deadly as they had hoped. But, while it seems to have retrenched the “orthodoxy” of the OBR for now, uncertainty abounds.

Hunt might not find the OBR to be so friendly at his next, pre-election, Budget, when he will hope to cash out his (disappearing) headroom to please voters and the OBR will be revising (likely downgrading) its forecast again.