Mini budget

Yesterday, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Kwasi Kwarteng, used the unusual Friday sitting of the House of Commons to make a ministerial statement on “The Growth Plan”.

Nicknamed the “mini Budget”, the Chancellor’s statement included a raft of measures — helpfully summarised here — that don’t seem quite so “mini”.

OBR blocked

Controversially, the Chancellor blocked the Office for Budget Responsibility from publishing a forecast, as it would normally do when a Budget is announced.

Labour shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves said this made the announcements look like a “menu without prices”, asking, “what has he got to hide?”

Tory MP Mel Stride, the Chair of the Treasury Select Committee, and a supporter of Rishi Sunak, warned:

“when the markets are getting twitchy about Government bonds and the currency is under pressure, now is the time for transparency and making it very clear that whatever tax cuts or otherwise there may be, they are done in a fiscally responsible manner… he should have come forward with an OBR forecast.”

Kwarteng committed to an OBR forecast before the end of the year and to meet with the Treasury Committee — two scrutiny bodies he will not want to alienate.

Who pays?

The Chancellor reiterated major support for consumers, businesses and suppliers dealing with the energy crisis, costing the Government around £60 billion in the first six months.

Kwarteng said of this plan:

“[It is] one of the most significant interventions the British state has ever made… on the side of the British people”.

Rachel Reeves said this showed “Labour has won the argument” on energy cost intervention.

But she immediately attacked the plans because they are funded through increased borrowing rather than increasing the windfall tax on energy companies, reiterating Labour’s slogan: “Who pays?”

Growth plan

Kwarteng announced the dawn of a “new era” — the very phrase prompted loud jeers from the Opposition Benches — to reverse the sluggish UK economy.

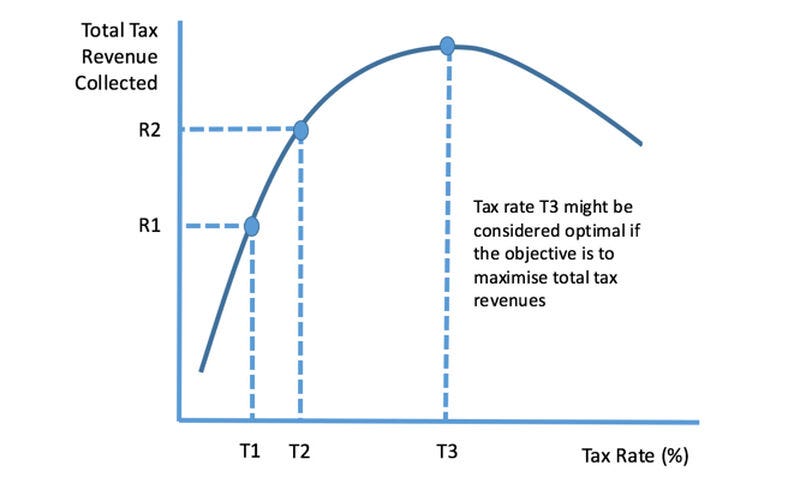

He set out an annual growth target of 2.5%, to turn a “vicious circle” of low growth and high taxes into a “virtuous cycle” of high growth and low taxes.

The Chancellor announced regulatory reforms to “get Britain building” and fiscal reforms to get capital investing, including:

Reforming planning regulation

Cutting stamp duty

Reforms to increase pension funds’ UK investments

Regional investment zones

100% tax relief on qualifying investments in plant and machinery

Scrapping bankers’ bonus cap

That last announcement sent the packed Opposition Benches into pandemonium.

Responding to criticisms that his mini Budget was merely giving handouts to his friends in corporate board rooms and the City, Kwarteng insisted his plans helped ordinary workers — in the short and long term — with measures including:

Energy cost support

Scrapping planned hike in National Insurance

Bringing forward reduction in the base rate of tax to 19 pence

Growth in capital investment leading to creation of more jobs

Growth in GDP leading to higher overall tax returns to fund public services

Kwarteng told the House that he hopes to make Britain an “entrepreneurial share-owning democracy”'; or, as Napoleon is reputed to have said, a nation of shopkeepers — with all the ambivalence that involves.

Big ideas or gambling?

Labour’s Rachel Reeves put forward a strong performance in her rebuttal. But, like the plan for growth itself, it was not without its contradictions.

On the one hand, Reeves said:

“The Prime Minister and Chancellor are like two desperate gamblers in a casino, chasing a losing run. The argument peddled by the Chancellor today is not a great new idea, or a game-changer, as he said, much though he would like us to think so.”

Yet, on the other hand, she argued that the plan was ideologically motivated:

“This statement is more than a clash of policies; it is a clash of ideas—two different ideas about how our country prospers.”

This gets to the difficulty of interpreting Liz Truss’ plan for Government. Is it a slap-dash and haphazard gamble or an ideologically-motivated attempt to make reality fit her plan? Or, as I asked during the leadership election, is she a bishop or a bookie?

Trickle-down

To the extent that Reeves sees an ideology behind the growth plan, it is “trickle-down economics”, something which the Opposition argue — with the support of President Biden — has long been proven not to work.

However, while it is not incumbent on Labour to put forward their own mini-Budget, it is not clear what their big idea is in this clash with “trickle-down economics”.

Expert advice or class war?

Some in the Labour party criticised Kwarteng for going against the economic establishment. They criticised him for sacking the top civil servant in the Treasury, avoiding the OBR forecasts and causing tension between the Treasury and the Bank of England.

Labour MP Emma Hardy warned that

“former Bank of England rate-setter Martin Weale… has said that the Government’s approach could “end in tears” with a run on the pound”.

And Barry Gardiner cited the fall in the value of the pound and the FTSE 100 as evidence of the business world’s lack of confidence in the Government’s plans.

(Remember what those institutions said about an incoming Labour Government under Corbyn?)

Conversely, other Labour MPs preferred a different tack.

Ian Lavery said the Chancellor declared “war on the trade unions”. Lloyd Russell-Moyle called it “class war” and former shadow Chancellor John McDonnell called it

“the most socially divisive Budget in a generation”.

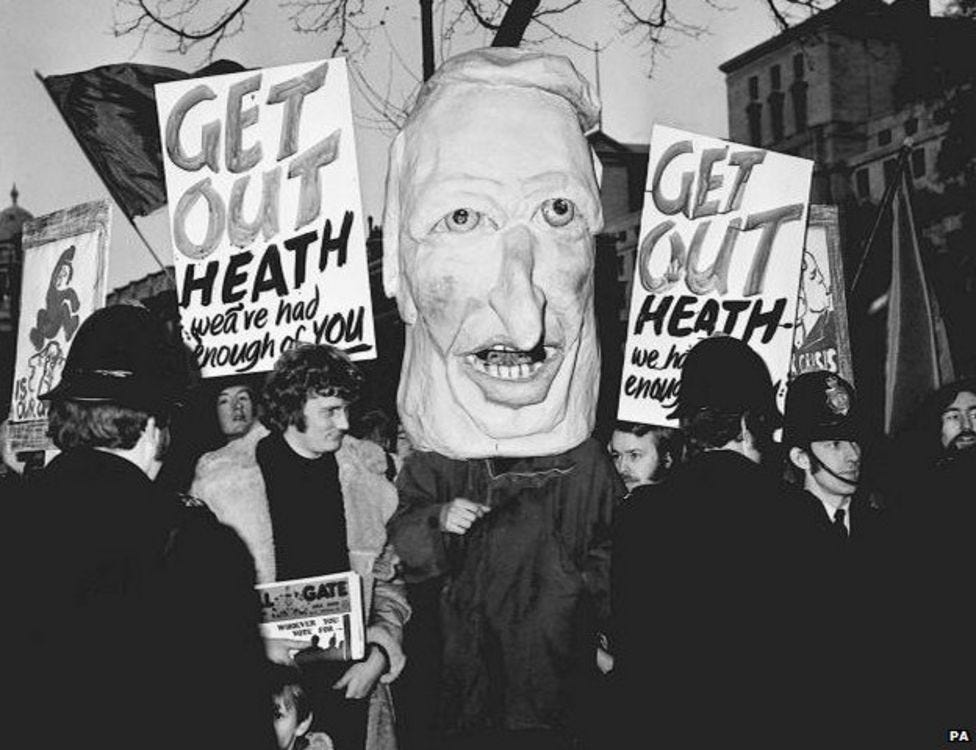

Barber boom

John McDonnell went on to cite the “Barber boom” of the early 1970s — when Tory Chancellor Anthony Barber tried to reach 10% growth in two years — as a precedent for a flawed government dash for growth through lower taxes and deregulation.

Labour MP Dame Margaret Hodge — no ally of McDonnell’s in the Labour Party — cited the same historical precedent, arguing that the “Barber boom” only led to a bust… and the fall of the Conservative Government.

Perhaps Labour are limbering up for a repeat of 1974, with the slogan “Who pays?” instead of “Who governs?” — a telling difference.

Kwarteng — whose academic pedigree shows he is no slouch when it comes to history — responded that the Barber boom was actually about loose monetary policy trying to drive the economy through demand. His plans, on the contrary, are about supply-side reform and are matched by the Bank of England’s fiscal tightening.

That’s one for the economic historians to weigh in on.

Limits to supply-side growth

As several MPs noted, the plan for growth exacerbates tensions between the Treasury and the Bank of England — despite Kwarteng’s protestations to the contrary.

Labour’s Nick Smith provocatively asked Kwarteng whether the Governor of the Bank of England will still have a job at Christmas.

The Government want to push the economy to grow and thereby avoid a recession, while the Bank of England wants to reign the economy in through increasing the interest rate — as they did on Thursday — to bring down inflation, even if that means going through a recession.

Moreover, as Labour’s Rushanara Ali pointed out, you can have all the supply side reforms you want, but if higher borrowing leads to higher inflation, mortgage-holders and small businesses will go under and demand will collapse.

Benefit slackers or care providers?

Another problem for a supply-side growth plan is labour (with a little L). As Tory MP James Cartlidge pointed out,

“to increase output he needs capacity in the labour market, which is extremely tight”.

Cartlidge warned of siren voices who would call to increase immigration to fill that need. Instead, he argued, the Government should focus on supporting those who have left the labour market back into work, especially mentioning

“those who have been written off, because of mild mental ill health, anxiety and all the rest of it”.

Of course, immigration levels may increase regardless — another political headache for the Conservatives.

Although he did not take up Cartlidge’s point about mental health, Kwarteng also wants to get Britain working, saying in response:

“There is a huge pool of talent that needs to be brought into the labour market.”

On this front he announced plans to sanction those on benefits who do not actively seek work and introduce minimum service requirements to hamper strike action in the transport sector. He said:

“we need to encourage people to join the labour market. We will make work pay by reducing people’s benefits if they do not fulfil their job search commitments.”

Labour MP Helen Hayes was one of several MPs to suggest that the problem was not the benefits system, but lack of affordable childcare.

She pointed out that “Four in 10 mothers have considered giving up work or cutting their hours because of the cost of childcare”, and asked:

“Why does the Chancellor think that bearing down with punitive sanctions on the lowest-paid working parents in part-time work will help them to increase their hours, when what they really need is an accessible, affordable childcare system fit for the 21st century?”

This was one line of attack to which the Chancellor conceded:

“The hon. Lady is absolutely right to identify childcare as a crucial issue, and I am looking forward to my right hon. Friend the Secretary of State for Education updating the House on that in the next few weeks.”

Whether one thinks the benefits system, mental health problems or childcare costs — or all three — are keeping people from seeking work, further pressure in an already tight labour market will only bring the Government’s plan for growth back into conflict with the Bank of England’s plans to cut inflation.

With pressure mounting from all sides, staying the course with this “plan for growth” will require nerves of steel from Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng.