What are Select Committees anyways?

The parliamentary reforms of 1979: a constitutional revolution?

Over the next few weeks, while MPs suffer this grey summer, I’m taking a look at Select Committees, which have been the focus of many of the reports published here in the past year.

As I have highlighted, over the past few years, the crisis over the role and function of Parliament — from powers to prorogue to partygate lies, fisticuffs in the voting lobbies and policy leaks to the media — has been seized upon by those who see the Select Committees as the solution to all our political woes, with their cross-party, consensual and evidence-based proceedings.

But where do the Select Committees come from and what powers do they really have?

They have become so naturalised as part of the workings of the Houses of Parliament, but it should not be forgotten that there were serious constitutional arguments made against them in the late 70s.

Next week, I will be drilling down into the Treasury Committee, which has been in the spotlight recently, given its role scrutinising the Bank of England and its Monetary Policy Committee.

The history

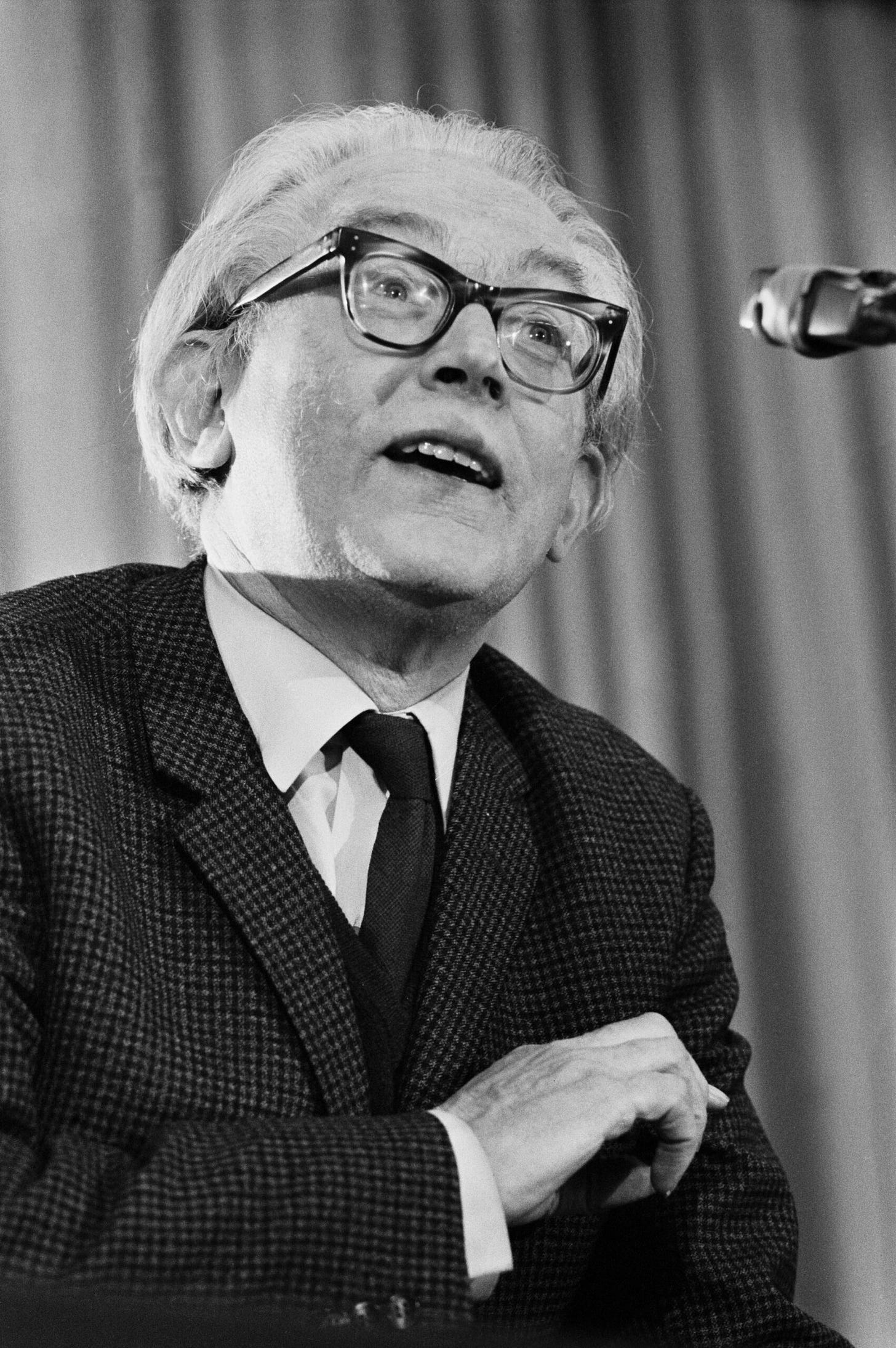

“In the time of Elizabeth I we had a much more developed Committee system than we have today.” — Conservative MP Norman St. John Stevas speaking in favour of Select Committee reform in 1979.

From the Committee on the Queen of Scotts (1572) to the Committee on the Confirmation of the Book of Common Prayer (1604) — both sadly no longer active — Parliament has a long history of using Select Committees (i.e. a committee not of the whole House) to investigate, probe and propose in relation to particular matters.

But the above mentioned bodies were quite different from the modern Select Committees we have today.

The first move towards the current system can be traced to the establishment of the Public Accounts Committee — still running today and sometimes known as the “mother” of Select Committees — under reforms introduced by Gladstone in 1861, the remit of which was first given by a Standing Order in 1862:

“That there shall be a standing Committee to be designated ‘The Committee of Public Accounts’; for the examination of the Accounts showing the appropriation of sums granted by Parliament to meet the Public Expenditure, to consist of nine members, who shall be nominated at the commencement of every Session, and of whom five shall be a quorum”.

As the “machinery of Government” transformed in the following decades, the scope of the Public Accounts Committee widened — not without controversy — and other irregular Committees were established to try to supplement its work, often playing a prominent role on specific legislative issues in the 19th century.

However, their role began to wane in the 20th century. As Bernard Crick wrote in The Reform of Parliament (1964):

“In the nineteenth century much important legislation was the direct result of the reports of Select Committees; they were major instruments of reform. But in this century there has been a steady decline in the numbers of Select Committees and, with a few notable exceptions, in their importance and influence… For one thing, Select Committees on matters of public policy have been thoroughly distrusted and disliked by the Whips; despite Government majorities on them, they have an awkward tendency to develop cross-bench sentiment, and a shocking habit of regarding the Executive as guilty until it is proved innocent.”

In the 1960s, changes made under Labour MP and Leader of the House Richard Crossman introduced three departmentally-related committees (Education and Science, Overseas Aid, Agriculture), three subject-related committees (Science and Technology, Race Relations and Immigration, Scottish Affairs), and converted the Estimates Committee into an Expenditure Committee with specialist sub-committees.

However, the distinction between subject and departmental committees was not successful. There was dissatisfaction with the unplanned nature of the system amid growing concern that the balance between the Executive and Parliament was weighted too heavily towards the former.

Those concerns led to the reforms proposed by the 1976-1978 Procedure Committee, which called for a permanent system of committees to, “examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the principal government departments”.

That call was taken up in the Conservative Party’s 1979 election manifesto and, only a month after taking office, Thatcher’s first Government introduced the departmental Select Committee system.

There have been modifications and developments from there, primarily those proposed by the Modernisation Committee in 2002, which gave Select Committees more money, more autonomy and a set of 10 core tasks in order to establish common objectives, as well as the so-called Scrutiny Unit to support their work.

However, the basic idea introduced in 1979 is still with us and still shapes the debates around Select Committees, their powers and their purpose.

As Conservative MP (soon to be Leader of the House under the new Government) Norman St. John Stevas said in the February 1979 debate on the proposed reforms:

“Long after the economic debates that bulk so large in contemporary consciousness have been assigned to the bound volumes of Hansard—and no oblivion can be deeper than that—what we decide about the ways that this House operates will be of living influence.”

The 1979 debates

The debate on the Procedure Committees proposals for departmental Select Committees took place on the 19th and 20th of February 1979.

The then-Opposition Conservatives were largely in favour of the reforms, while the Labour Party, then in Government, resisted them. However, there were divisions within the parties and when it came to a vote there was no mandated party-line.

Speaking for the Opposition, Stevas — who after the election in May would become Leader of the House — noted:

“Truly there is no one more conservative than a retired radical.”

He was referring to Michael Foot, then Leader of the House and soon to be the “Left wing” Leader of the Opposition, who argued against the reforms.

The impetus for reform came from what Stevas called a “widespread public anxiety” that Parliament was not performing its function of scrutinising the Executive — and the ever-expanding modern bureaucracy that came with it.

“We have, in effect, a professional Government and we still have an amateur legislature.”

He insisted — against objections — that departmental Select Committees would not cause a demotion of the House of Commons Chamber, and that the Committees would not be “American-style Congressional Committees” with powers to compel witnesses and promote policy.

The changes, he said, would be “radical”, but “not revolutionary”: they would preserve the principle of ministerial responsibility, simply reinforcing the scrutiny function of Parliament.

Like Stevas, Michael Foot based his remarks on the root issue the reforms sought to address, which was, according to the Procedure Committee report:

“that the balance of advantage between Parliament and Government in the day to day working of the Constitution is now weighed in favour of the Government to a degree which arouses widespread anxiety and is inimical to the proper working of our parliamentary democracy.”

However, Foot argued (anticipating arguments for Brexit), if the primary concern is an imbalance in favour of the Executive, then the primary issue to address is the entry of the UK into the EEC (now the European Union), which gave up legislative autonomy in a manner favouring the Executive.

Foot’s basic argument against the Select Committees was that they would diminish the importance of and access to the Chamber for MPs, undermining their primary democratic function.

“It is not only the question of major debates but the fact that a Member of Parliament is able to exercise his right—even if he does not do so—to have access to the House and put a question or raise a matter in a debate, or that it is known that he is able to do so. There is also the fact that he is able to put extremely unpopular views—often views held only by him. That access to this place is of paramount importance.”

Foot feared an Americanisation of Parliament:

“the more powerful the committees have become in the United States, the more debased or ineffective have become the House of Representatives and, to some degree, the Senate.”

Foot also argued that the Committees would — despite all their critical posturing — become “a shield for the Departments” and that top Civil Servants would support their establishment precisely because of that.

When it was put to him that there was no other way of holding top bureaucrats accountable, Foot held on to the old-fashioned parliamentary view that the Minister should hold the bureaucrats accountable, and that any Minister who did not dominate his civil servants should be booted out.

Railing against “the blob” may be the purview of the political Right today, but it wasn’t always that way.

Foot concluded that the proposals were indeed “radical”, and should therefore be rejected or at least shunted to the next Parliament (after the May election). After all, they were

“the most far-reaching series of proposals for dealing with parliamentary procedure that has been presented for 30 years.”

Well, the Conservatives swept to office in May, and in June Stevas was Leader of the House and Foot his shadow.

When Stevas proposed the reforms to the House of Commons in the June debate he went further than Foot had five months earlier, declaring:

“we are embarking upon a series of changes that could constitute the most important parliamentary reforms of the century”.

The debate in June had shifted from that of February. The constitutional concerns of Michael Foot had been left behind.

The focus now was on the modernisation of Parliament for the age of science and technology.

Labour MP Frank Hooley argued:

“My belief is that the trouble with Whitehall and the Ministries is that they are not sufficiently equipped to deal with the vast complexity of the problems that modern government throws on them. One of the great advantages of the Select Committee system is that it provides a technique for drawing on the vast amount of expertise which lies outside Whitehall, the Civil Service and the Ministries.”

Yet, on the same grounds, Conservative MP Ian Lloyd opposed the reforms. He was worried about the abolition of the pre-existing Science and Technology Committee.

“My conclusion is that the reforms might bring the House into line with the needs of the 1950s, which probably should have been done a long time ago, but bear little relevance to the needs of the 1980s, when decisions in Government and industry will be built into the information systems which are designed and continuously developed precisely for these purposes… We are in the silicon age, an age in which technology is utterly dependent on, and indissolubly wedded to, science.”

The debates today around Parliament and the role of Select Committees have not moved on much from the terms set by those debates in 1979.

In the shift from February (when Michael Foot opposed the reforms) to June (when Stevas carried them through under the new Tory majority), the constitutional arguments against Select Committees fell away — and they haven’t returned.

Next week, I will take a look at the development of the Treasury Committee from 1979 to the present, especially looking at how it dropped its focus on the civil service in 1995 and took up its scrutiny of the Bank of England in 1997.