Legislation Breakdown (2)

The key Government Bills that will shape the debate on Foreign Affairs & Defence this autumn

Welcome to Parliamentary Insight, and a big thank you for subscribing!

This is the third of our intro briefings this week, before Parliament returns on Monday. You can read more about this project here.

Starting next week, I will be posting a regular overview of the week ahead every Monday, a Foreign Affairs & Defence newsletter every Thursday, and an Economics & Finance newsletter every Friday.

Following yesterday’s breakdown of upcoming Economics & Finance legislation, this newsletter breaks down key Government Bills relating to Foreign Affairs & Defence that will be debated in the coming weeks in Parliament. Tomorrow we will look at the parliamentary record of our likely next Prime Minister Liz Truss.

Foreign Affairs & Defence

1. Northern Ireland Protocol Bill

The Point

This Bill passed through the Commons in July and is now due its Second Reading in the Lords. It is highly controversial because it disapplies the protocol determining the movement of goods and services across the border in Northern Ireland set out in the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement, and it makes provisions for alternative domestic laws.

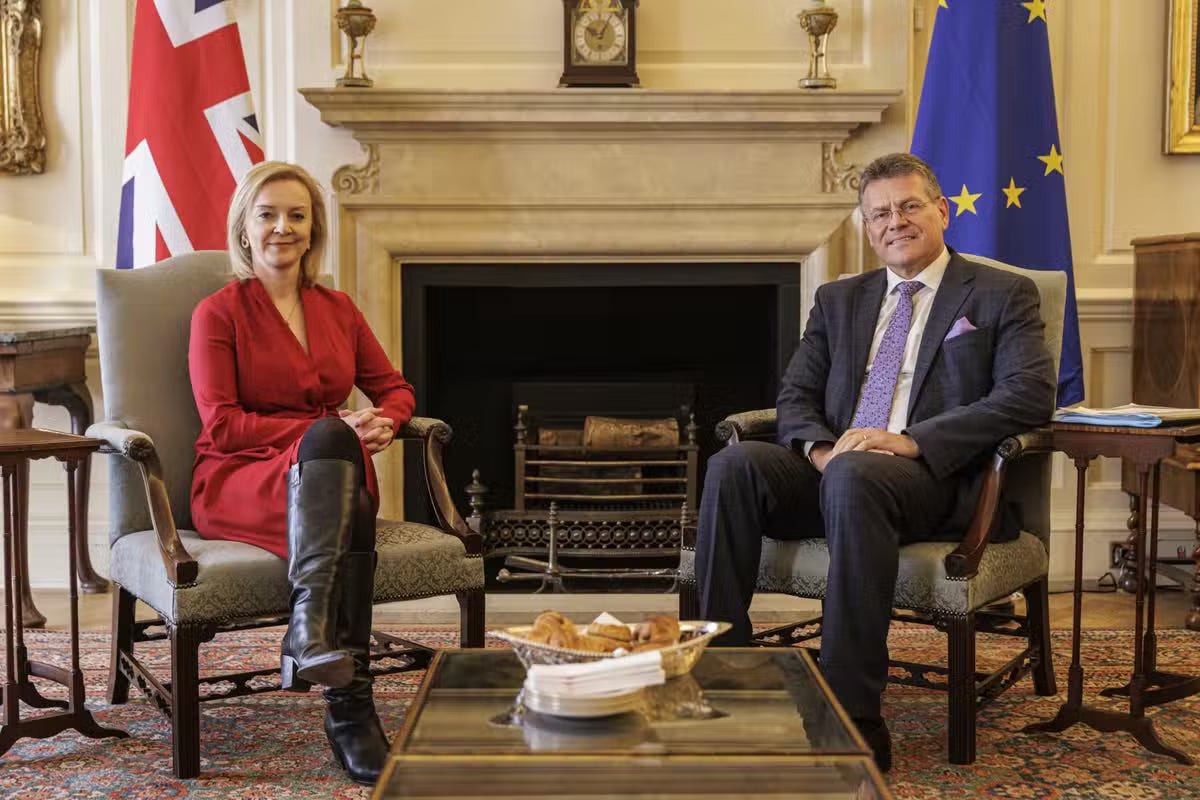

The Bill follows the breakdown of negotiations between Foreign Secretary (and candidate for Prime Minister) Liz Truss and Maroš Šefčovič, Vice-President of the European Commission. The former still maintains that a negotiated settlement is her preferred outcome.

The Debate

The protocol had been criticised by Conservatives and Unionists for putting a border through the Irish Sea, separating Northern Ireland from the rest of the United Kingdom. The situation has been exacerbated by the breakdown of the power-sharing agreement in the Northern Ireland Assembly. Unionists place the blame on the protocol, which they see as tacit recognition of an all-Ireland economy.

In a fiery debate on Third Reading in the Commons, SDLP MP Colum Eastwood said:

“This Bill is a sop to the DUP and a campaigning tool for the Foreign Secretary in the Conservative party leadership election. If it is driven through, the only likely outcome is a trade dispute with the European Union. Well, good luck to the next Prime Minister if they want to go into the general election with prices going even higher than they already are.”

Labour, concerned not to appear too pro-EU, went with the more lawyerly argument, articulated by Stephen Doughty, that the Bill “disregards the UK’s international legal obligations and threatens to throw Britain’s global reputation into disrepute”.

The Bill is set to face strong resistance in the Lords, where there is still deep opposition to Brexit, as well as concerns about the powers delegated to the Minister. The Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee has argued that:

“The Bill represents as stark a transfer of power from Parliament to the Executive as we have seen throughout the Brexit process.”

But, as Boris Johnson demonstrated, it is a risky business for the Lords to challenge the Commons, especially over Brexit.

The Context

If Liz Truss becomes Prime Minister on Monday, events may escalate before the Lords get around to debating this. Truss has indicated she may trigger Article 16 within days, allowing the UK to take “safeguarding” measures before the Bill goes through the Lords. The UK has until 15 September to respond to legal action filed by the EU in response to the tabling of this Bill back in June.

As Isabel Hardman noted on the BBC’s “Westminster Hour” on Sunday night, this issue could shape a Liz Truss Cabinet.

“[Liz Truss] wants unity from her front bench. So, anyone who is a bit softer on the protocol, a bit more concerned about the moves she is taking, probably won’t make it into a top job, because she sees that that sort of division will make it much harder to have the sort of negotiated compromise that Conor [Burns, Minister of State for Northern Ireland] and others are hoping for.”

In an excellent piece for Politico last night, Cristina Gallardo called this Truss’ first big parliamentary battle, and noted:

“As ever, parliamentary tactics will be key.”

Parliamentary Insight will be there to keep you up to date with the debate when the Lords get their teeth into it.

2. National Security Bill

The Point

The Bill follows a review of the Official Secrets Act 1989 by the Law Commission. It sets out provisions for more stringent laws against the disclosure of sensitive information to foreign agents.

The Bill updates the powers of the intelligence services to deal with espionage in the digital age, while the focus is redrawn away from terrorist threats to “hostile state actors”. Whereas disclosing protected information under the 1989 Act carries a maximum sentence of two years, disclosing protected information under this Bill carries a maximum sentence of life. However, the Bill leaves the 1989 Act in tact.

The Debate

Picking up on such contradictions, in the Second Reading debate backbench MPs complained that the Bill did not replace the 1989 Act and was often loosely worded. Senior Tory MP David Davis pulled back the curtain on the Whitehall mandarins, observing:

“The enforcement agencies’ lawyers will have done most of the drafting, so it is no surprise that it leans towards the state, and no surprise that parts of it are drafted in vague terms.”

MPs also pointed out that at least two of the Law Commission’s recommendations were missing:

a register for “foreign agents”, forcing intelligence agents to publicly register their affiliations

a “public interest defence” for whistleblowers or journalists charged with illegally releasing sensitive Government information to foreign agents.

While Matrix Chambers and Mishcon de Reya argued in their briefing paper that a public interest defence is necessary to protect civil liberties and align British law with article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, the MPs backing such provisions as amendments had different intentions, arguing for it to be drawn as narrowly as possible, precisely to rule out many potential use cases. As Tory MP Robert Buckland QC put it while arguing for a public interest defence:

“None of us wants to see Julian Assange and his type carry sway here; we just think that we need to do something before it is done to us.”

The Context

Concerns around civil liberties were muted against the backdrop of Julian Assange’s imprisonment and extradition to the United States, as well as increased tensions with Russia and China. As George Grylls reported in The Times this week, Liz Truss, who has long been a foreign policy hawk, looks set to “declare China an official threat for the first time”.

The development of this Bill also needs to be understood in the context of claims that Russia interfered in Brexit and in the 2016 US election. Despite all the evidence showing that “Russiagate” claims were built on sand — as Matt Taibbi has documented on his Substack — there has nonetheless been a ramp up of rhetoric and action against national security concerns on both sides of the pond.

With Labour likely to support a bullish stance on Russia and China, it will be left to a few lonely Backbenchers to raise concerns about the trade-off between freedom and security. On Second Reading, self-styled libertarian Steve Baker explained that his interest in the Bill “relates to the general assault on liberty that we saw after 9/11.”

He raised concerns about the broad wording of clause 23 of the Bill, which disapplies the Serious Crime Act 2007 to intelligence and armed forces personnel when acting abroad.

However, he had to concede that when it comes to

“compromising... values by giving the state the power to restrict liberty without a conviction... I have lost that argument.”

MPs will continue their scrutiny of the Bill in Committee next Tuesday.

3. Bill of Rights Bill

The Point

This major piece of post-Brexit legislation bears considering as part of foreign relations because of its international implications, for example regarding the deportation of foreign criminals and, more importantly, the impact of rulings of the European Court of Human Rights on UK courts and Parliament.

The Debate

While the Bill retains the European Convention on Human Rights, to which the UK will remain party, the introduction stipulates that:

“judgments, decisions and interim measures of the European Court of Human Rights— (a) are not part of domestic law, and (b) do not affect the right of Parliament to legislate”.

However, according to Liberty’s response to the Ministry of Justice’s pre-legislative consultation,

“The decisions of Strasbourg are binding and States Parties are obliged to implement them (Article 46 of the Convention).”

Therefore, there is further potential for international disputes over the applicability of Strasbourg rulings, if this is not clarified.

The Context

The Bill’s title invokes the 1689 Bill of Rights, which is (at least, in theory) central to the British constitution and parliamentary system. The introduction underscores Britain’s “Parliamentary democracy”, claiming to reinstate the sovereignty of Parliament post-Brexit, by rebalancing

“the relationship between courts in the United Kingdom, the European Court of Human Rights and Parliament”.

But opponents of the Bill dispute that the sovereignty of Parliament was ever limited by the European Court of Human Rights. Moreover, strong opposition to many parts of this Bill will be fuelled by the international climate of increased tensions with Russia and China, coupled with closer relations with the Gulf states. Needless to say, all of those countries are widely condemned for their records on human rights.

Parliamentary Insight will be following closely when the Bill comes up for Second Reading in the Commons on Monday 12 September.